LLVM IR and Go

In this post, we’ll look at how to build Go programs – such as compilers and static analysis tools – that interact with the LLVM compiler framework using the LLVM IR assembly language.

TL;DR we wrote a library for interacting with LLVM IR in pure Go, see links to code and example projects.

Quick primer on LLVM IR

(For those already familiar with LLVM IR, feel free to jump to the next section).

LLVM IR is a low-level intermediate representation used by the LLVM compiler framework. You can think of LLVM IR as a platform-independent assembly language with an infinite number of function local registers.

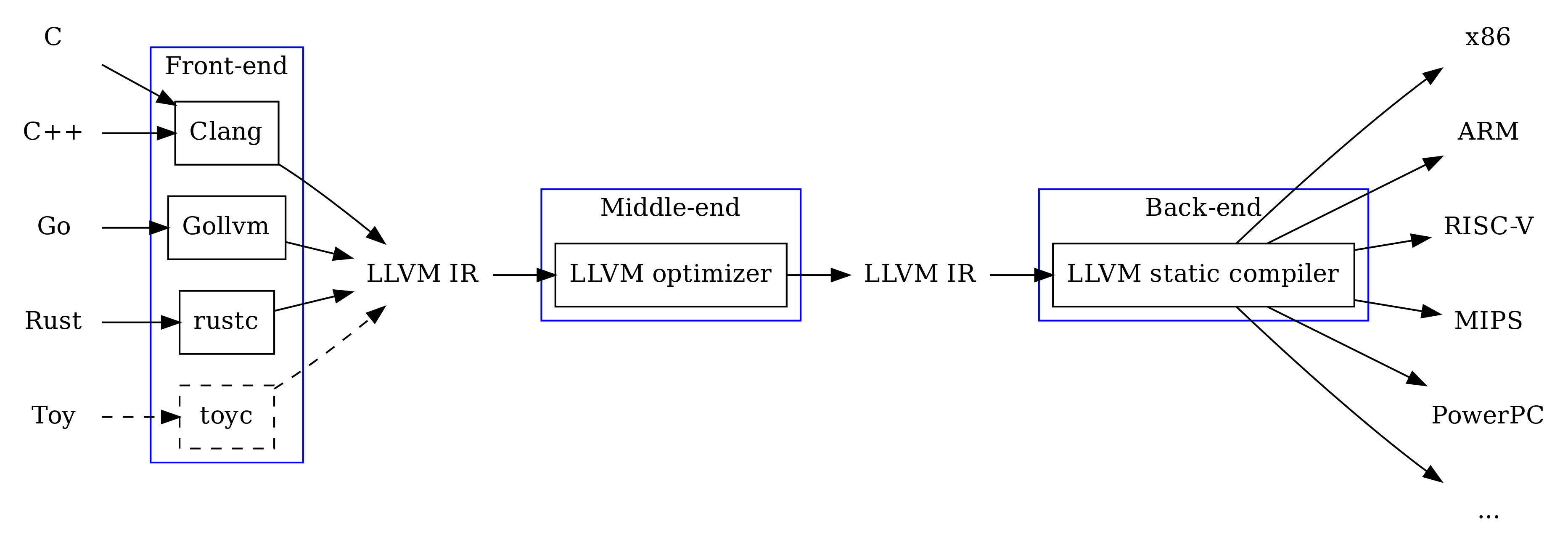

When developing compilers there are huge benefits with compiling your source language to an intermediate representation (IR)1 instead of compiling directly to a target architecture (e.g. x86). As many optimization techniques are general (e.g. dead code elimination, constant propagation), these optimization passes may be performed directly on the IR level and thus shared between all targets2.

Compilers are therefore often split into three components, the front-end, middle-end and back-end; each with a specific task that takes IR as input and/or produces IR as output.

- Front-end: compiles source language to IR.

- Middle-end: optimizes IR.

- Back-end: compiles IR to machine code.

Example program in LLVM IR assembly

To get a glimpse of what LLVM IR assembly may look like, lets consider the following C program.

|

|

Using Clang3, the above C code compiles to the following LLVM IR assembly.

|

|

By looking at the LLVM IR assembly above, we may observe a few noteworthy details about LLVM IR, namely:

- LLVM IR is statically typed (i.e. 32-bit integer values are denoted with the

i32type). - Local variables are scoped to each function (i.e.

%1in the@mainfunction is different from%1in the@ffunction). - Unnamed (temporary) registers are assigned local IDs (e.g.

%1,%2) from an incrementing counter in each function. - Each function may use an infinite number of registers (i.e. we are not limited to 32 general purpose registers).

- Global identifiers (e.g.

@f) and local identifiers (e.g.%a,%1) are distinguished by their prefix (@and%, respectively). - Most instructions do what you’d think,

mulperforms multiplication,addaddition, etc. - Line comments are prefixed with

;as is quite common for assembly languages.

The structure of LLMV IR assembly

The contents of an LLVM IR assembly file denotes a module. A module contains zero or more top-level entities, such as global variables and functions.

A function declaration contains zero basic blocks and a function definition contains one or more basic blocks (i.e. the body of the function).

A more detailed example of an LLVM IR module is given below, including the global definition @foo and the function definition @f containing three basic blocks (%entry, %block_1 and %block_2).

|

|

Basic block

A basic block is a sequence of zero or more non-branching instructions followed by a branching instruction (referred to as the terminator instruction). The key idea behind a basic block is that if a single instruction of the basic block is executed, then all instructions of the basic block are executed. This notion simplifies control flow analysis.

Instruction

An instruction is a non-branching LLVM IR instruction, usually performing a computation or accessing memory (e.g. add, load), but not changing the control flow of the program.

Terminator instruction

A terminator instruction is at the end of each basic block, and determines where to transfer control flow once the basic block finishes executing. For instance ret terminators returns control flow back to the caller function, and br terminators branches control flow either conditionally or unconditionally.

Static Single Assignment form

One very important property of LLVM IR is that it is in SSA-form (Static Single Assignment), which essentially means that each register is assigned exactly once. This property simplifies data flow analysis.

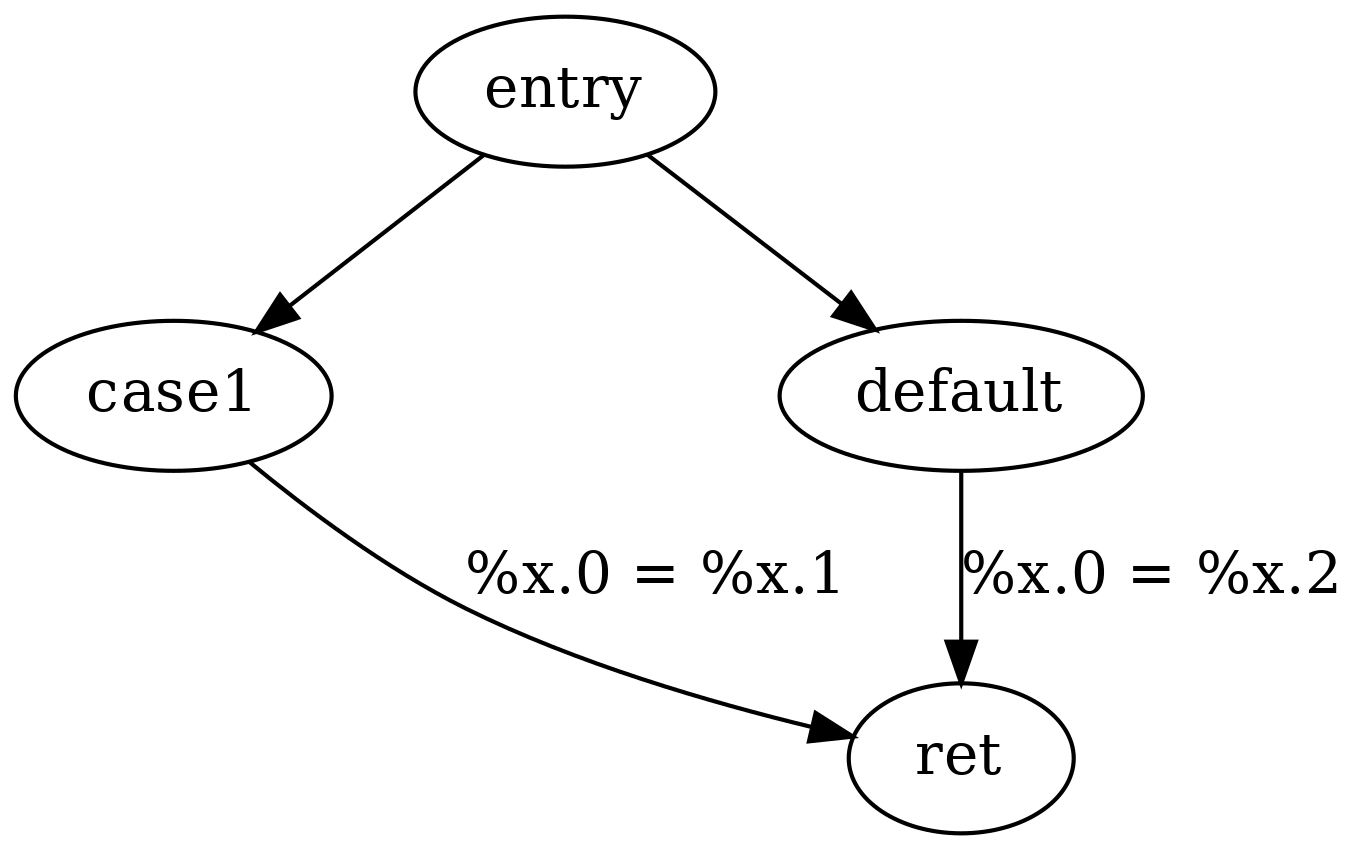

To handle variables that are assigned more than once in the original source code, a notion of phi instructions are used in LLVM IR. A phi instruction essentially returns one value from a set of incoming values, based on the control flow path taken during execution to reach the phi instruction. Each incoming value is therefore associated with a predecessor basic block.

For a concrete example, consider the following LLVM IR function.

|

|

The phi instruction (sometimes referred to as phi nodes) in the above example essentially models the set of possible incoming values as distinct assignment statements, exactly one of which is executed based on the control flow path taken to reach the basic block of the phi instruction during execution. One way to illustrate the corresponding data flow is as follows:

In general, when developing compilers which translates source code into LLVM IR, all local variables of the source code may be transformed into SSA-form, with the exception of variables of which the address is taken.

To simplify the implementation of LLVM front-ends, one recommendation is to model local variables in the source language as memory allocated variables (using alloca), model assignments to local variables as store to memory, and uses of local variables as load from memory. The reason for this is that it may be non-trivial to directly translate a source language into LLVM IR in SSA-form. As long as the memory accesses follows certain patters, we may then rely on the mem2reg LLVM optimization pass to translate memory allocate local variables to registers in SSA-form (using phi nodes where necessary).

LLVM IR library in pure Go

The two main libraries for working with LLVM IR in Go are:

- llvm.org/llvm/bindings/go/llvm: the official LLVM bindings for the Go programming language.

- github.com/llir/llvm: a pure Go library for interacting with LLVM IR.

The official LLVM bindings for Go uses Cgo to provide access to the rich and powerful API of the LLVM compiler framework, while the llir/llvm project is entirely written in Go and relies on LLVM IR to interact with the LLVM compiler framework.

This post focuses on llir/llvm, but should generalize to working with other libraries as well.

Why write a new library?

The primary motivation for developing a pure Go library for interacting with LLVM IR was to make it more fun to code compilers and static analysis tools that rely on and interact with the LLVM compiler framework. In part because the compile time of projects relying on the official LLVM bindings for Go could be quite substantial (Thanks to @aykevl, the author of TinyGo, there are now ways to speed up the compile time by dynamically linking against a system-installed version of LLVM4).

Another leading motivation was to try and design an idiomatic Go API from the ground up. The main difference between the API of the LLVM bindings for Go and llir/llvm is how LLVM values are modelled. In the LLVM bindings for Go, LLVM values are modelled as a concrete struct type, which essentially contains every possible method of every possible LLVM value. My personal experience with using this API is that it was difficult to know what subsets of methods you were allowed to invoke for a given value. For instance, to retrieve the Opcode of an instruction, you’d invoke the InstructionOpcode method – which is quite intuitive. However, if you happen to invoke the Opcode method instead (which is used to retrieve the Opcode of constant expressions), you’d get the runtime errors “cast<Ty>() argument of incompatible type!”.

The llir/llvm library was therefore designed to provide compile time guarantees by further relying on the Go type system. LLVM values in llir/llvm are modelled as an interface type. This approach only exposes the minimum set of methods shared by all values, and if you want to access more specific methods or fields, you’d use a type switch (as illustrated in the analysis example below).

Usage examples

Now, lets consider a few concrete usage examples. Given that we have a library to work with, what may we wish to do with LLVM IR?

Firstly, we may want to parse LLVM IR produced by other tools, such as Clang and the LLVM optimizer opt (see the input example below).

Secondly, we may want to process LLVM IR to perform analysis of our own (e.g. custom optimization passes) or implement interpreters and Just-in-Time compilers (see the analysis example below).

Thirdly, we may want to produce LLVM IR to be consumed by other tools. This is the approach taken when developing a front-end for a new programming language (see the output example below).

Input example - Parsing LLVM IR

|

|

Analysis example - Processing LLVM IR

|

|

Output example - Producing LLVM IR

|

|

Closing notes

The design and implementation of llir/llvm has been guided by a community of people who have contributed – not only by writing code – but through shared discussions, pair-programming sessions, bug hunting, profiling investigations, and most of all, a curiosity for learning and taking on exciting challenges.

One particularly challenging part of the llir/llvm project has been to construct an EBNF grammar for LLVM IR covering the entire LLVM IR assembly language as of LLVM v7.0. This was challenging, not because the process itself is difficult, but because there existed no official grammar covering the entire language. Several community projects have attempted to define a formal grammar for LLVM IR assembly, but these have, to the best of our knowledge, only covered subsets of the language.

The exciting part of having a grammar for LLVM IR is that it enables a lot of interesting projects. For instance, generating syntactically valid LLVM IR assembly to be used for fuzzing tools and libraries consuming LLVM IR (the same approach as taken by GoSmith). This could be used for cross-validation efforts between LLVM projects implemented in different languages, and also help tease out potential security vulnerabilities and bugs in implementations.

The future is bright, happy hacking!

Further resources

There is a very well written chapter about LLVM by Chris Lattner – who wrote the initial design of LLVM – in the Architecture of Open Source Applications book.

The Implement a language with LLVM tutorial – often referred to as the Kaleidoscope tutorial – provides great detail on how to implement a simple programming language that compiles to LLVM IR. It goes through the main tasks involved in writing a front-end for LLVM, including lexing, parsing and code generation.

For anyone interested in writing compilers targeting LLVM IR, the Mapping High Level Constructs to LLVM IR gitbook is warmly recommended.

A good set of slides is LLVM, in Great Detail, which provides an overview of important concepts in LLVM IR, gives an introduction to the LLVM C++ API, and in particular describes very useful LLVM optimization passes.

The official Go bindings for LLVM is a good fit for many projects, as they expose the LLVM C API which is very powerful and also quite stable.

A good complement to this post is the article An introduction to LLVM in Go.

- The idea of using an IR in compilers is wide spread. GCC uses GIMPLE, Roslyn uses CIL, and LLVM uses LLVM IR. [return]

- Using an IR thus reduces the number of compiler combinations required for n source languages (front-ends) and m target architectures (back-ends) from n * m to n + m. [return]

- Compile C to LLVM IR using:

clang -S -emit-llvm -o foo.ll foo.c. [return] - The github.com/aykevl/go-llvm project provides Go bindings to a system-installed LLVM. [return]